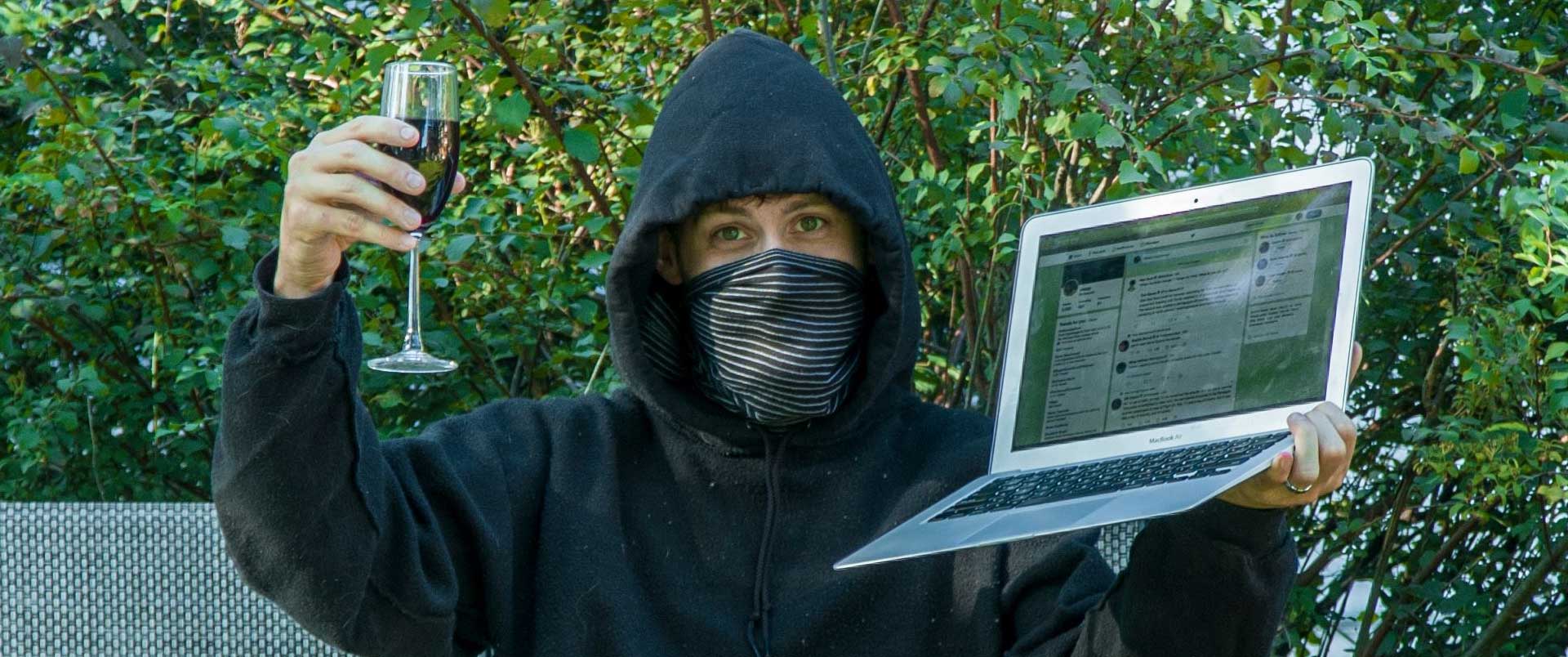

In the not too distant past, I was frequently accused of being a left-wing extremist. More recently, I’ve been accused of supporting the alt-right. Neither of these things is true, but the absurd accusations are a grimly amusing example of how polarized and extreme our political discourse has become. A couple of weeks back, I decided to write a short video about this very subject, and the result is NaziMaker — a minute-and-a-half-long satirical infomercial about an easy way to demonize those you disagree with. (It is published as the 46th entry in our web series, Evil Grin Gift Box.)

Within about ten minutes of posting it on Twitter and tagging some of the public figures who appear in it, Dave Rubin retweeted it, followed by Claire Lehmann, Joe Rogan, Ben Shapiro, and many others, who drove it past half a million views across various platforms within just a couple of days. Most of the feedback has been positive, but I’ve also had people sending a fair number of accusations and questions my way, so I’ll do my best to address them here, taking the opportunity to point out larger problems with political discourse that have become magnified along the way.

Group Identity Often Trumps Everything

Because NaziMaker uses a man dressed as an antifa member as its antihero, many people have assumed we are conservatives orchestrating an attack on “the left”, or worse, “supporting alt-right narratives.”

As I noted in a followup post, both Jesup (the actor dressed as an anarchist) and I are liberals who wanted to criticize a specific bipartisan problem: the use of ad hominem attacks to dismiss political opponents without addressing their concerns or arguments. The short could have easily been called SnowflakeMaker, using a guy in a red Trump hat as its antihero. But when it comes to namecalling, the far left commonly uses more inflammatory labels. The consequences of being dubbed a Nazi, a fascist, or a white supremacist are demonstrably worse than being called a cuck, a snowflake, or a soyboy.

The result is a video that criticizes name-calling by using the far-left as a negative example. When it began rapidly gaining popularity, both sides of the political spectrum raced to identify the authors as either liberals or conservatives, and made up their minds about the content based on their conclusions.

In one particularly amusing example, a Twitter user initially dismissed the video as being made by conservatives. Upon being told it was created by liberals, he fired back, “they must be fake liberals then.”

This behavior highlights one of the most troubling social trends I’ve noticed recently — the tendency to assess a piece of content solely based on a judgment of the author's group identity. Of course, a certain amount of judgment based on an author's background is sensible. It's perfectly reasonable to try to understand the political perspective and motives from which a particular author is writing. However, it's become more common to see people immediately approve or dismiss content based solely upon learning an author’s political leanings, or based on labels culled from biased headlines. "Oh, this is written by Jordan Peterson? Isn't he a right-winger? And a sexist? No thanks!" The result is often a failure to consider an author's content on its own merits, and to write off legitimate arguments wholesale based on deeming the author to be an enemy. Rather than asking “Is the argument sound?” the question becomes, “Is the author on my side?”

This is evident on a small scale in the reception to NaziMaker, in which some people are able to easily dismiss the piece by assigning "enemy" labels to its authors, despite those labels being drastically inaccurate.

The Unacceptability of In-Group Criticism

Many have noticed the levels of hostility and tribalism in the US have been gradually increasing over the last few years, but one particular event drew my attention to that problem with marked clarity. On February 1, 2017, right-wing provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos was scheduled to speak at UC Berkeley. In response, an anarchist group within the mass of left-wing protesters caused over $100,000 in property damage and physically attacked and injured several attendees. (Details of the physical attacks are laid out in detail in Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt's book, The Coddling of the American Mind.)

The justification given by protesters (and by some of my friends defending them), was that Milo was a Nazi, a fascist, and a white supremacist. While Milo has said and done many terrible things, based on the information available at the time, there was no evidence to believe any of those labels were accurate — they were simply hyperbole used to make an already-detestable person more detestable. Of course, as in the NaziMaker video, these hyperbolic labels were extended to the Milo event's attendees, dubbing them "supporters of fascism" in order to justify physical violence against them.

The media offered plenty of criticism of antifa, mostly focusing on the fact that the attacks had actually given Milo access to a national platform as a result of the news coverage. But many in the left-wing activist sphere around me vocally defended the anarchists. A melodramatic exhortation from one such person directed at me read, “This is a war. Side up.”

The response to NaziMaker from some on the left has been similar -- essentially, "Why would you attack your own team?" Meanwhile several on the right seem unable to understand that the criticism of ad hominem arguments applies to them as well. The result is a clear view of a common problem: the unwillingness to criticize, or accept criticism of, one’s own group.

Of course, for either side to improve, it must be willing to accept critique and make changes based on it. And who better to offer criticism than members of one’s own group? Flaws are often clearer from the inside, and the critique offered is frequently gentler than it would be coming from an adversary.

For the left, those who are truly liberal-minded need to draw a line between themselves and extremists who believe violence and mass demonization of people based on group identity is justified. We don't need anymore Nazi makers. Essentially the same thing can be said of the right, in that conservatives need to separate themselves from those who want to pack every member of "the left" into a box marked "Libtard-Cucklord-Soyboy-Socialists."

NaziMaker is about as lighthearted a critique of failed dialogue as possible. As futile as it sounds to ask for meaningful results from something so silly, I do hope it provokes reflection about dismissive labeling as much as it evokes laughter.